Measuring pH with Natural Indicators at Home: A Fun Science Experiment for Primary Students

December 23, 2025

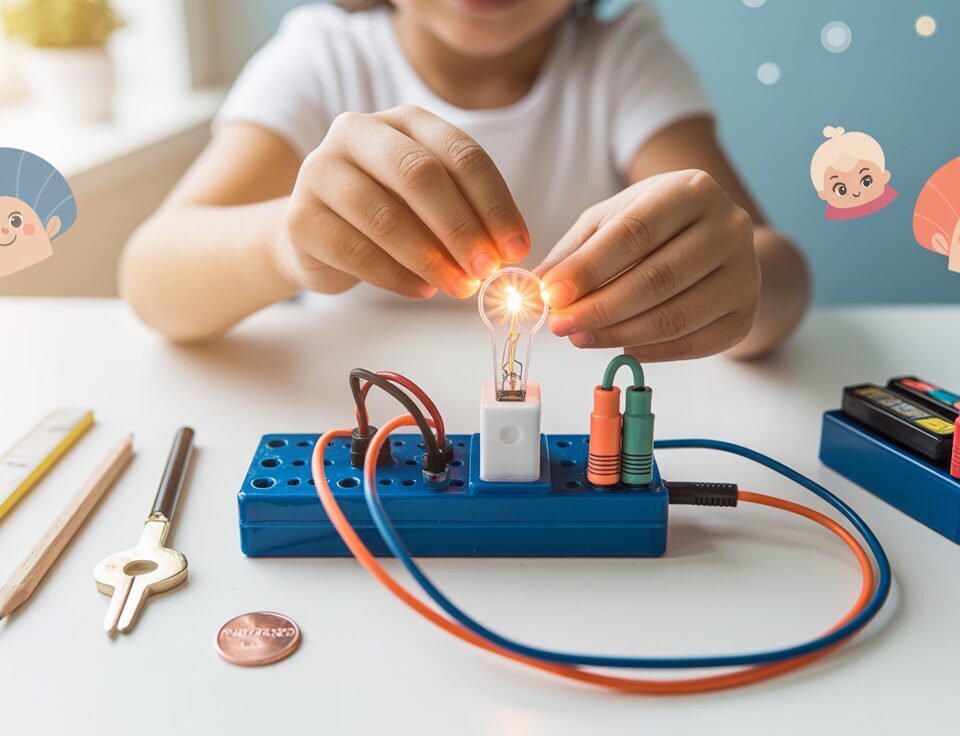

Electrical Conductors & Insulators Test Kit Guide for Primary Science Students

December 25, 2025Table Of Contents

- What Is an Experiment Logbook?

- Why Experiment Logbooks Matter for Primary Students

- Essential Components of an Experiment Logbook

- Free Experiment Logbook Template

- How to Use Your Experiment Logbook: Step-by-Step Guide

- Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Tips for Maintaining an Excellent Logbook

- Building Confident Young Scientists

If your child has a science project coming up—whether for school assignments, science competitions, or PSLE preparation—an experiment logbook is an essential tool that often gets overlooked. Many students rush through experiments without proper documentation, only to struggle when it’s time to present their findings or write their reports. A well-maintained experiment logbook doesn’t just help students organize their thoughts; it teaches them critical thinking, develops their observation skills, and builds the scientific mindset they’ll use throughout their academic journey.

At Seashell Academy by Suntown Education Centre, we’ve seen countless students transform their approach to science when they learn to document their experiments properly. Our holistic learning approach emphasizes not just memorizing facts, but understanding processes and developing genuine scientific curiosity. An experiment logbook is where this transformation becomes visible—where scattered observations become structured knowledge, and where questions lead to discoveries.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll walk you through everything you need to know about creating and using an experiment logbook template. Whether your child is in Primary 4 exploring their first independent science project or a Primary 6 student preparing for PSLE Science practicals, this guide will help them document their scientific journey with confidence and clarity.

Experiment Logbook Essentials

Your Complete Guide to Scientific Documentation

📚What Is an Experiment Logbook?

A dedicated scientific record documenting observations, hypotheses, procedures, data, and conclusions in chronological order. It’s not just a report—it’s your child’s scientific thinking process captured in real-time.

7 Essential Components

Why Logbooks Matter for Primary Students

🎓 Academic Benefits

- Supports PSLE Science requirements

- Develops analytical thinking skills

- Strengthens memory retention

- Enables effective exam revision

🌟 Life Skills Development

- Builds organizational habits

- Teaches attention to detail

- Nurtures intellectual honesty

- Develops systematic thinking

Step-by-Step Process

Pre-Experiment Planning

Complete research question, hypothesis, and materials list before starting

Document Procedure

Write numbered steps as you perform the experiment

Record in Real-Time

Write observations immediately while details are fresh

Organize Data

Use tables and charts for measurements and numerical data

Analyze Thoughtfully

Look for patterns and relationships in your findings

Draw Honest Conclusions

Answer the research question based on evidence collected

Reflect & Learn

Consider what to improve and what questions arose

⚠️ Common Mistakes to Avoid

❌ Recording After the Fact

Always document during the experiment, not from memory later

❌ Hiding “Wrong” Results

Unexpected findings teach more than expected ones

❌ Being Too Vague

Use precise measurements and specific descriptions

❌ Making It Too Perfect

A working document with corrections shows authentic science

💎 Key Takeaway

An experiment logbook isn’t just about recording data—it’s about developing critical thinking, building scientific confidence, and nurturing the curiosity that drives lifelong learning success.

What Is an Experiment Logbook?

An experiment logbook (also called a laboratory notebook or science journal) is a dedicated record where students document every aspect of their scientific investigations. Think of it as a scientist’s diary—a place where observations, questions, hypotheses, procedures, data, and conclusions all come together in chronological order. Unlike a final science report that presents polished results, a logbook captures the authentic, messy process of scientific discovery as it happens.

For Primary students, an experiment logbook serves multiple purposes beyond simple record-keeping. It’s a thinking tool that helps them organize their thoughts before conducting experiments, a memory aid that preserves important details they might otherwise forget, and a learning resource they can review when preparing for assessments. Most importantly, it teaches them that science isn’t about getting the “right” answer immediately—it’s about asking good questions, making careful observations, and learning from both successful and unexpected results.

The best experiment logbooks are honest and complete. They include failed attempts, revised hypotheses, and even mistakes—because these are often where the most valuable learning happens. When students understand that their logbook is a safe space for exploration rather than a graded assignment requiring perfection, they develop the resilience and growth mindset that characterizes successful learners.

Why Experiment Logbooks Matter for Primary Students

Many parents wonder whether experiment logbooks are really necessary for younger students. After all, won’t they learn these skills later in secondary school or beyond? Our experience at Seashell Academy tells a different story. Students who develop strong documentation habits early consistently demonstrate better scientific understanding and perform more confidently in practical assessments.

Academic Benefits

From a purely academic perspective, experiment logbooks directly support PSLE Science requirements. The PSLE Science syllabus emphasizes experimental skills, data interpretation, and the ability to explain scientific concepts—all areas where a well-maintained logbook provides essential practice. When students regularly record observations and analyze results, they develop the analytical thinking skills that appear throughout the Mathematics programme as well, particularly in data handling and problem-solving sections.

Beyond examination preparation, logbooks help students retain information more effectively. Writing observations by hand (rather than just watching demonstrations) engages different parts of the brain and strengthens memory formation. Students who maintain experiment logbooks can review their previous work before tests, reinforcing concepts through their own documented experiences rather than just textbook definitions.

Life Skills Development

The benefits extend far beyond science class. Maintaining an experiment logbook teaches organizational skills, attention to detail, and systematic thinking—competencies that support learning across all subjects. These habits are particularly valuable as students progress through Primary 4, 5, and 6, when academic demands intensify and effective study strategies become crucial.

Perhaps most importantly, experiment logbooks nurture intellectual honesty and integrity. When students learn to document what they actually observed rather than what they think they should have seen, they develop authenticity in their academic work. This foundation of honest inquiry serves them well throughout their educational journey and beyond.

Essential Components of an Experiment Logbook

A comprehensive experiment logbook contains several key sections that work together to create a complete scientific record. Understanding these components helps students know what to document and why each element matters.

Identification Information

Every logbook entry should begin with basic identification details that provide context for the experiment. This includes the date, the student’s name, and a descriptive title for the experiment. The title should be specific enough that someone reading the logbook months later can immediately understand what investigation took place. For example, “Plant Experiment” is too vague, while “Investigating How Different Amounts of Sunlight Affect Bean Plant Growth” clearly communicates the focus.

Research Question and Hypothesis

Before conducting any experiment, students should clearly state what they’re trying to discover. The research question frames the investigation, while the hypothesis provides a testable prediction based on existing knowledge. For Primary students, we encourage simple, clear formulations: “Does the amount of water affect how fast seeds sprout?” followed by “I think seeds with more water will sprout faster because plants need water to grow.”

This section teaches students to think before experimenting—a crucial skill that prevents aimless tinkering and promotes purposeful investigation. It also creates a baseline against which they can later evaluate their results.

Materials List

A complete list of all materials and equipment used ensures the experiment could be replicated. Students should include specific details: not just “seeds” but “10 green bean seeds,” not just “containers” but “5 plastic cups, 200ml capacity.” This precision develops attention to detail and helps students understand that scientific reproducibility requires specificity.

Procedure

The procedure section documents exactly what the student did, written in numbered steps that someone else could follow. We teach students to write procedures in the past tense (“I placed the seeds in the cup” rather than “Place the seeds in the cup”) because they’re documenting what actually happened, not writing instructions. This subtle distinction reinforces that a logbook is a record of real events.

Including diagrams or sketches alongside written procedures helps visual learners and creates a more complete record. Students don’t need artistic skill—simple labeled drawings showing experimental setup are often more informative than paragraphs of text.

Observations and Data

This is where the science happens. Students should record everything they observe using their senses (except taste, for safety reasons), including unexpected occurrences. Data can take many forms: measurements recorded in tables, written descriptions of changes, photographs, sketches, or even sound recordings for certain experiments.

We encourage students to separate observation (what they actually perceive) from interpretation (what they think it means). For example, “The plant stem bent toward the window” is an observation, while “The plant needs light and grew toward it” is an interpretation. Both belong in the logbook, but students should understand the difference.

Analysis and Conclusion

After collecting data, students should analyze what they found and draw conclusions. Did the results support their hypothesis? Why or why not? What patterns emerged from the data? This section develops critical thinking as students learn to evaluate evidence and form logical arguments based on their observations.

Equally important is documenting what didn’t work or what they would change next time. These reflections demonstrate scientific maturity and often lead to deeper understanding than simply reporting expected results.

Free Experiment Logbook Template

To help your child get started, here’s a simple template that includes all essential components. This template works for most Primary-level science experiments and can be adapted based on specific project requirements.

Experiment Logbook Entry Template

Date: _______________________

Student Name: _______________________

Experiment Title: _______________________

Research Question:

What do I want to find out?

_______________________

Hypothesis:

What do I think will happen and why?

_______________________

Materials Needed:

- _______________________

- _______________________

- _______________________

Procedure (What I Did):

- _______________________

- _______________________

- _______________________

Diagrams/Sketches:

[Space for drawings of experimental setup]

Observations and Data:

What did I see, hear, smell, or feel?

What measurements did I take?

_______________________

Data Table (if applicable):

[Create table with appropriate columns for your experiment]

Analysis:

What patterns do I notice in my data?

_______________________

Conclusion:

What did I learn? Was my hypothesis correct?

_______________________

Reflection:

What would I do differently next time?

What new questions do I have?

_______________________

Students can copy this template into a dedicated notebook or print multiple copies to keep in a binder. For younger students, parents might pre-print templates with more space for writing. Older students preparing for PSLE might add additional sections for variables (independent, dependent, and controlled) to align with the scientific method terminology they’ll encounter in examinations.

How to Use Your Experiment Logbook: Step-by-Step Guide

Having a template is just the beginning. The real value comes from using it consistently and thoughtfully throughout the experimental process. Here’s how to guide your child through each stage of maintaining their experiment logbook.

1. Pre-Experiment Planning – Before touching any materials, students should complete the identification, research question, hypothesis, and materials sections. This planning phase encourages them to think critically about what they’re investigating and why. We often see students want to dive straight into “doing” the experiment, but this preparatory thinking is where scientific reasoning develops. Encourage your child to discuss their hypothesis with you: “Why do you think that will happen?” This dialogue deepens their engagement and helps them articulate their reasoning more clearly in their written hypothesis.

2. Writing the Procedure – As students set up their experiment, they should document each step in sequence. For younger students or first-time experimenters, it helps to do a “practice run” where they perform the steps while saying them aloud, then write down what they did. This approach is similar to the mind-mapping techniques we use in our P4 Chinese Programme, where breaking down complex processes into smaller steps makes them more manageable. Remind students to include important details like measurements, timing, and safety precautions taken.

3. Recording Observations in Real-Time – This is perhaps the most critical skill. Students should write observations while the experiment is happening or immediately afterward, when details are fresh. Waiting until later often results in forgotten details or unconsciously adjusted memories. Teach your child to use their senses actively: What do you see changing? What do you hear? How does it feel? For experiments that take place over several days (like plant growth studies), establish a regular observation schedule—same time each day—and make logbook entries part of the routine.

4. Organizing Data Clearly – When experiments generate numerical data or measurements, tables are usually the clearest presentation method. Help your child create simple tables with appropriate column headings. For example, a plant growth experiment might have columns for “Day,” “Plant Height (cm),” “Number of Leaves,” and “Observations.” Students should fill in tables neatly and double-check their recorded numbers. If a mistake is made, teach them to draw a single line through the error (so it’s still readable) and write the correction nearby—scientists never completely erase data, as even mistakes can provide valuable information.

5. Analyzing Results Thoughtfully – After data collection is complete, students should look for patterns, trends, and relationships in their data. Guide them with questions: “Which plant grew the most? Which grew the least? Why might that be?” For Primary students, analysis doesn’t need to be complex—identifying that “plants with more sunlight grew taller” is a perfectly valid conclusion. The goal is teaching them to look at evidence and draw logical inferences, not to produce graduate-level statistical analysis.

6. Writing Honest Conclusions – The conclusion should answer the original research question and state whether the hypothesis was supported by the data. If results contradicted the hypothesis, that’s not a failure—it’s science! Help your child understand that unexpected results often teach us more than expected ones. Their conclusion should acknowledge this: “I thought plants with more water would grow faster, but my experiment showed that too much water actually made the plants grow slower. This might be because…” This kind of thoughtful reflection demonstrates genuine scientific thinking.

7. Reflecting for Future Learning – The reflection section is where students consider what they’d do differently next time or what new questions their experiment raised. This metacognitive practice—thinking about their own thinking—builds the self-awareness that characterizes strong learners. It also helps students see science as an ongoing process rather than isolated activities with definitive endings.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even with the best intentions, students (and parents helping them) often fall into common pitfalls when maintaining experiment logbooks. Being aware of these mistakes helps you avoid them.

Recording Observations After the Fact

One of the most frequent mistakes is conducting the entire experiment and then trying to remember what happened while filling in the logbook later. Memory is unreliable, and details get lost or unconsciously altered to fit expectations. The logbook should be present during the experiment, not completed afterward as homework. If your child forgets to bring their logbook to an experiment, have them write observations on scrap paper immediately and transfer them to the official logbook as soon as possible, noting that they were recorded retrospectively.

Changing or Hiding “Wrong” Results

Sometimes students get results that don’t match their hypothesis or expectations, and they’re tempted to adjust their data or hide observations that don’t fit the pattern they want to see. This completely undermines the purpose of scientific investigation. Create an environment where your child feels safe recording authentic observations, even if they’re unexpected. Emphasize that finding something different from what you predicted is often more interesting and educational than confirming what you already thought.

Being Too Vague

Entries like “The plant grew” or “The water got hot” lack the specificity needed for scientific documentation. Encourage precise language and measurements: “The plant grew 2.5 cm taller” or “The water temperature increased from 22°C to 45°C.” This precision is a habit that develops over time, so be patient with younger students while consistently modeling and encouraging more specific observations.

Focusing Only on Final Results

A complete logbook documents the entire experimental journey, including false starts, equipment problems, and revised plans. If the first attempt failed because materials weren’t prepared properly, that should be documented. If the procedure needed adjustment partway through, both the original plan and the modification should be recorded. This comprehensive documentation teaches students that science is iterative and that learning comes from the entire process, not just the final outcome.

Making It Too Perfect

Some students (or parents) want the logbook to look beautiful, with perfect handwriting, elaborate decorations, and no cross-outs. While neatness is good, an experiment logbook is a working document, not an art project. It’s more important that it’s complete and honest than that it’s pretty. A logbook with crossed-out mistakes, taped-in corrections, and smudged fingerprints shows authentic scientific work. Save the polished presentation for the final science project report or display board.

Tips for Maintaining an Excellent Logbook

Beyond avoiding mistakes, here are positive strategies that help students develop strong documentation habits and create logbooks that truly support their learning.

Use permanent ink: Pencil can smudge and fade over time, and it’s also easier to erase—which can tempt students to remove “mistakes.” Using pen (except for initial sketches or diagrams) creates a permanent record and reinforces that all observations are valuable. Blue or black ink is standard, though colored pens can be used to highlight different types of information or distinguish between multiple trials.

Include visual documentation: Photographs, sketches, and diagrams often capture information that’s difficult to describe in words. Students don’t need artistic talent—simple labeled drawings showing experimental setup, equipment arrangement, or observed changes are extremely valuable. For ongoing experiments, sequential photos showing change over time create powerful visual records. These can be printed and taped into physical logbooks or included digitally if using an electronic format.

Date every entry: Even if conducting multiple observations in one day, note the specific time for each entry. This chronological record helps students see patterns that emerge over time and provides context for understanding their results. It also develops the professional habit of time-stamping observations, which is standard practice in all scientific fields.

Write in first person: Students should use “I” in their logbooks: “I observed,” “I measured,” “I noticed.” This personal voice reinforces that they’re documenting their own direct experience and thinking. It also makes the writing more natural and less stilted than trying to use passive voice (“It was observed that…”), which many students find unnecessarily complicated.

Create a consistent routine: For multi-day experiments, establish regular observation times and stick to them. Making logbook entries a habitual part of the experimental routine ensures students don’t forget and helps them collect comparable data. This routine-building also supports the structured learning approaches we emphasize in our P5 Chinese Programme and across all subjects.

Review previous entries before continuing: Before each observation session, have your child briefly review their previous logbook entries. This helps them notice patterns, remember important details, and think about what to watch for in the current observation. It transforms the logbook from a passive record into an active thinking tool.

Ask “why” and “what if” questions: Encourage your child to include wondering and questioning in their logbook entries. “I wonder why this plant grew faster than the others” or “What if I tried this with a different type of seed?” These questions demonstrate scientific curiosity and often lead to follow-up investigations that deepen understanding.

Share and discuss the logbook: Periodically, sit down with your child and have them walk you through their logbook entries, explaining what they did and what they found. This verbal explanation reinforces their learning and helps them practice the communication skills they’ll need when presenting their work. It also gives you insight into their scientific thinking and opportunities to ask guiding questions that deepen their analysis.

Building Confident Young Scientists

An experiment logbook is far more than a school requirement or a collection of observations—it’s a powerful tool for developing the scientific mindset that serves students throughout their academic careers and beyond. When your child learns to document their experiments systematically, ask meaningful questions, analyze evidence objectively, and draw logical conclusions, they’re developing critical thinking skills that apply to every subject and every challenge they’ll face.

At Seashell Academy by Suntown Education Centre, we see these skills blossom when students engage authentically with scientific inquiry. The confidence that comes from conducting real experiments, making genuine discoveries, and documenting the journey transforms students from passive receivers of information into active learners who question, explore, and construct their own understanding. This is the heart of our programme philosophy—nurturing not just academic competence, but genuine love for learning.

Whether your child is just beginning their science journey in Primary 4 or preparing for PSLE assessments in Primary 6, developing strong experiment documentation habits now will serve them well. The logbook becomes a record of their growth as a thinker, a testament to their curiosity, and a foundation for the scientific literacy they’ll carry into secondary school and beyond.

Remember that perfection isn’t the goal—authentic engagement is. Some logbook entries will be more complete than others, some experiments will fail spectacularly, and some conclusions will need revision. That’s not just okay; it’s exactly how science works. By supporting your child in maintaining an honest, thorough experiment logbook, you’re teaching them that learning is a process, mistakes are valuable, and curiosity leads to understanding. These lessons extend far beyond the science lab, shaping resilient, thoughtful learners who approach challenges with confidence and creativity.

Help Your Child Develop Strong Scientific Thinking Skills

At Seashell Academy by Suntown Education Centre, we don’t just teach science facts—we nurture confident, curious learners who understand how to think scientifically. Our experienced MOE-trained educators guide Primary students through hands-on investigations, proper documentation techniques, and critical analysis that builds both academic excellence and genuine love for learning.

Whether your child needs support with PSLE Science preparation or you want to develop their experimental skills and scientific confidence, our structured yet nurturing approach helps every student reach their full potential.

Discover how we can support your child’s scientific journey and academic growth.